Mutual 12 resident reflects on time spent in Tanzania, Africa

This is the first of a multi-part series authored by Mutual 1 resident Deanna Sciaraffa about the experiences of Mutual 3 resident Evie Chapman in Tanzania, Africa. The rest of her story will be published in future editions of the LW Weekly.

by Deanna Sciaraffa

LW contributor

When I learned that Mutual 3 resident Evie Chapman had climbed Mt. Kilimanjaro, I knew immediately that I wanted to hear her story firsthand. Afterall, how many of us can say we know someone who has climbed that mountain let alone lived vicariously through the listening to the story? After she sketched some of the details I was fascinated and told her I thought she should share her experiences by writing about them. Her answer, “Oh, no, I don’t write like that,” shifted me into another gear that drove me to ask her if I could write her story for her. She gracefully consented and we were off.

Our three interview sessions led to this paper which in no way reveals the enjoyment I had noting Evie’s reminiscences and commentaries, as well as her infrequent offhanded humor.

Special thanks go to Craig g Chapman for his excellent and patient editing skills, and my writing partner Ann McGee, whose astute critique led to clarification and enhancing descriptiveness.

I am most grateful to Evie for allowing me to relive with her one of her life’s milestones. I have enjoyed myself immensely and credit her with the inspiration to reflect, appreciate, understand, and, yes, dream.

Prologue

In 1967, 20-year-old Evie Atkinson was contemplating what she wanted to do with her future. Her inclination was to follow her brothers and sisters into Mennonite social service, a tradition that began during World War II when Mennonite conscientious objectors were offered alternate forms of volunteerism for the benefit of the country. She decided to offer her service in Arizona as a bookkeeper and was momentarily traumatized when her request was met with a proposal to assign her to Africa for three years. For a lively young woman who had travelled no farther than Ohio or North Carolina, around 1,000 miles from her home in Pennsylvania, the thought of flying over 12,000 miles to another country filled her with angst. Evie cried throughout the night because she did not want to go to Africa, but her strong beliefs soon prevailed over her stubbornness.

Never say no to God. Pay attention to His directions. I’d better go to Africa.

According to Mennonite doctrine, Evie was first required to pass an aptitude test administered by a board of Mennonite pastors. She did not expect to succeed and was stunned when she was told she had scored well on the examination.

Again, God must really want me to go to Africa.

There were other hoops she had to jump through that included changes in her destination, starting with Ethiopia as a bookkeeper at a Bible bookstore to finally being assigned to Tanzania as a bookkeeper in church offices where she would work for the African bishop, African treasurer, and African secretary. Evie accepted the assignment under duress with God even as she chose to follow His word.

Ultimately in 1967 Evie, an independent, non-conformist 21-year-old young woman from the peaceful town of Quakertown, Pennsylvania, was on her way to Africa where she would live and work as a bookkeeper. A New African State that had just three years prior gained its independence when Tanzania was formed into a union between Tanganyika and Zanzibar. In the same year as her departure, the Tanzanian government had declared itself a socialistic society with the adoption of the Arusha Declaration that was designed to ensure a classless society. Her bookkeeper duties would serve the Mennonite church just when the country was transitioning from American missionaries overseeing their own funds to turning them over to the Africans for them to gain economic freedom. She would have time to consider her new life during the three-day flight from Philadelphia to JFK to Holland and Amsterdam, to Germany and Greece, and finally to Nairobi. Acquiescence finally overwhelmed her during the Nairobi fly-over when she recognized the native huts she had seen in photographs of the area. Beneath her wings lay her new reality.

Enculturation

Upon her arrival to Nairobi, mission personnel including a driver and his female partner met Evie at the airport in a tiny Fiat loaded with supplies. They would drive from Nairobi to Musoma, 209 miles, for one whole day during which time Evie would get her first introduction to Africa. Going to the bathroom during the long road trip involved stepping outside to find a bush where there were no people lingering nearby, an unsuccessful chore for Evie. Consequently, she spent the entire ride in pain caused by her voluntary urinary retention and being jolted around inside the tiny car.

Here I am, no friends or anyone known. I’m all alone. ‘Just me and God.

Finally, they arrived at a house where she was able to use a real restroom. It was then that she decided she was not prepared mentally or emotionally for the emerging cultural shock.

She realized her practical knowledge might prove to be contrary to the values and beliefs that prevailed in her new environment. The basic norms that governed over her life in Quakertown included a childhood without summersaults or any sports participation throughout school because girls don’t do that. Females wore dresses only and head coverings over their required long hair, and they never wore jewelry. Dancing was prohibited and the only music Evie ever heard was a capella hymns sung exclusively in church. Her home was ruled by her passive-aggressive nonverbal father who sometimes could be very loud without ever offering positive reinforcement. Hence it was that Evie was prepared to obey rules and remain subservient as a woman.

The day after her arrival to Nairobi, Evie was taken for a ride to the Nairobi wild game park by a 60-year-old old-time missionary named Elsie. It was Evie’s first experience at a game park. While they were driving, the car became stuck on a large boulder. A lion pride could be seen lolling 15 feet away from the car. Unnoticed to either of them was a game warden standing nearby.

“Evie, step out of the car and give it a foot push so we can move off this rock.”

Evie knew that lions on the loose were dangerous but readily complied to Elsie’s directions by extricating herself out the car, and while still standing on one leg behind the open car door she heard a man’s angry voice, “You! Get back in the car. I’ll take care of this.” Once she was inside the car the game warden gave it a little push to successfully free it off the boulder. He was very angry, telling Evie that he was concerned for her safety amidst the nearby pride. Evie was embarrassed and realized that in trying to behave and obey she was the one on the rock, stuck between it and a hard place, some 300 miles from her imagined destination.

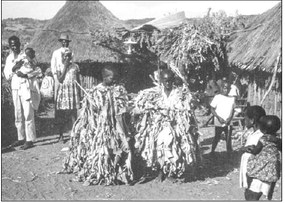

Evie was pleasantly surprised at Musoma’s location on the edge of Lake Victoria where one British passenger ship arrived once a week. But she was less impressed when the Africans laughed at her and called the Mission Board crazy for sending a young girl to work in their village. There was little she could do to defend herself other than accept her situation and do her best.

Her living quarters were in a housing compound that included mission personnel residing in four different houses. One house was occupied by a senior couple, Dorothy and George Smoker, who attended to the pastors and taught theology. The second house was occupied by the church secretary, Mauma. Phoebe, a church evangelist, lived in the third house. She rode throughout the district in a VW bus driven by a guide. The fourth house was the residence of Bishop Kisare.

The pastor couple, Joseph and Edie Shenk, lived in a house beyond the compound. Evie was assigned to live with Dorothy and George in a small guest cottage attached to the rear of their house. She was immediately enthralled by the sound of the people’s music, drifting quietly from the direction of their village.

Evie’s challenging adjustments to her new arrangement were intensified by her new lifestyle which included going from an active 21-year-old woman with something to do every night to having nothing to do for nightly entertainment. Generated electricity and lighting were provided to the houses from 7:30-10:30 p.m., at which time all the electricity was turned-off. On Evie’s first night in her home, she sat-up all night with a lit flashlight for company and security.

On the next morning, her first day on the job, George handed Evie a poster bearing a long prayer written in Swahili, telling her she was to memorize it by the following morning. Five minutes into horror caused by her lack of knowledge of the Swahili language, George playfully let her know that he was just kidding. His sense of humor carried over to his stories about unwanted household snakes and the coiled cobra his wife, Dorothy, discovered on the floor next to their bed. Soon afterward George offset his teasing by making her a battery-powered nightlight. But that was after her second night in her new dwelling when she was terrified because of the stories George had told her about snakes hanging from the ceiling and crawling on the floor next to the bed, something she never experienced in Quakertown.

Evie remained freaked-out as she grew into her new reality.

Ascofu Kisare was the head of the church and Evie’s main boss. She regarded him as a great father for his 12 children and a great husband to his one wife. In the beginning, Ascofu gave her the name, Mtoto, “The Kid,” but over time as their relationship grew into one of trust, he changed her name to, Binti, “Daughter.”

This practice inspired mutual confidence.

Evie Atkinson's view of Lake Victoria.

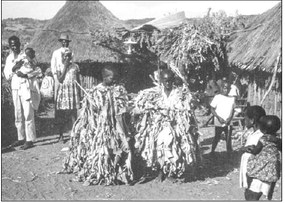

Banana peel painting of Musoma at the edge of Lake Victoria.