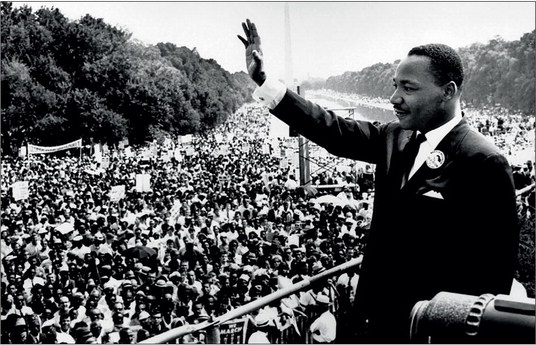

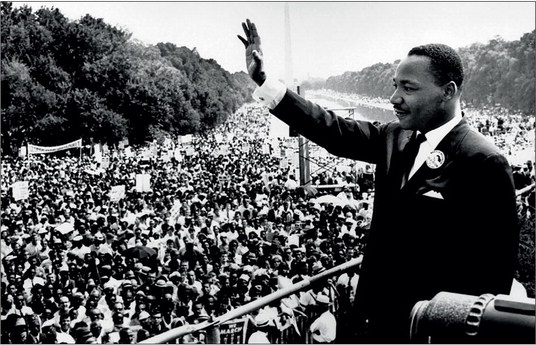

‘You could hear a pin drop’ when MLK began to speak

In honor of Black History Month, this story recounts one woman’s experiences at the March on Washington on Aug. 28, 1963. It was there that charismatic young civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. delivered the 16-minute “I Have a Dream” speech that has become one of the most famous orations of the civil rights movement and human history.

by Ruth Osborn

managing editor

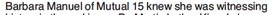

Barbara Manuel of Mutual 15 was one of the 250,000 people who gathered in Washington, D.C., for the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

It was the day that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech.

She was one slight woman in the vast crowd, which was assembled around the reflecting pool in front of the Lincoln Memorial and on lawns and under trees, trying to evade the oppressive heat of that Aug. 28 day.

history in the making as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. began his “I Have a Dream” speech in 1963.

Ruth Osborn She does not remember the name of her companion, a Freedom Rider who accompanied her on a chartered bus to stand against the ongoing inequalities faced by African Americans 100 years after slavery had been abolished.

But she will never forget the feel of the day, the power of seeing Dr. King, then 34 years old, and her first experience of racial hatred, which happened on her way home.

“I had never experienced the Jim Crow discrimination of the south until after I took part in the March on Washington,” she said.

The blistering heat overshadows all her memories of that day. Barbara, then a 20-year-old clerk for a large insurance company, and her friend boarded a bus in New Jersey and rode for four hours before arriving in Washington, D.C., where thousands of like-minded people of all color, age and ilk streamed toward the Lincoln Memorial.

“One of the things I remember most about the trip was the unity. It was incredible. I had never experienced anything like it. People were sharing drinks, food, pillows. It was happy sharing, accommodating. I was very moved.”

Hundreds of buses lined the Washington boulevards surrounding the National Mall, and her driver made sure his passengers knew exactly when and where to meet after the speech. And then the girls were on their own.

“There were so many people,” said Barbara. “The numbers were beyond anyone’s dreams. There were no television advertisements. People just came.”

March organizers had hoped 100,000 people would attend, according to History.com. In the end, more than twice that number flooded into the nation’s capital, making it the largest demonstration in U.S. history to that date.

“All these Black people in one place, a real brotherhood. There were a lot of white people there, too,” said Barbara. “They all had a single purpose—to be heard.”

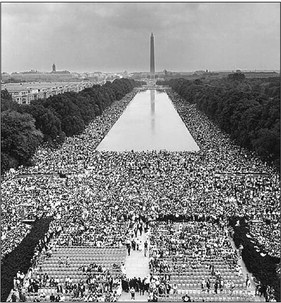

Plenty of celebrities were in the crowd and on stage. Actor and singer Harry Belafonte lined up Queen of Gospel Mahalia Jackson, Odetta and Marian Anderson for the concert on the National Mall at the end of the march, but he also included white folk artists Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, and Peter, Paul and Mary.

Odetta’s monumental voice rang out when she sang “I’m on My Way,” and Marian Anderson sang “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands.” Twentytwo- year-old Bob Dylan sang “Only a Pawn in Their Game” and “When the Ship Comes In.” Peter, Paul and Mary gave a stirring rendition of “Blowin’ in the Wind.” Joan Baez traveled from Spain to be at the march, singing “All My Trials” for the crowd.

At the core of Barbara’s memory is the speech itself.

It was electrifying. When Dr. King started talking, the crowd fell silent.

“You could hear a pin drop,” she said. “When he walked out, it felt like a dream because I had heard so much about him, his greatness, and I never dreamed I would actually see him. I knew I was a part of history.

“It was so moving, so touching, so spiritual, like I was getting baptized in the River Jordan.”

King had debuted the phrase “I have a dream” in his speeches at least nine months before the March on Washington and used it several times since then, according to History.com.

His advisers had discouraged him from repeating the same theme, and he had reportedly drafted a version of the speech that didn’t include it. After staying up until 4 a.m. to fine-tune what he hoped would have the same impact as the Gettysburg Address, King went off-script for his most iconic words.

As he spoke that day, Mahalia Jackson shouted at him to “tell them about the dream, Martin.”

King pushed the prepared speech to one side of the podium and spoke from the heart, sharing his vision with the world. Most of the second half of the speech, including the “I have a dream” refrain, was delivered extemporaneously.

King used the phrase “I have a dream” eight times, including: “I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character. I have a dream today.”

He ended with: “Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!”

Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered on April 4, 1968, at the age of 38, in Memphis, Tennessee.

In 2002, the Library of Congress added the “I Have a Dream” speech to the United States National Recording Registry.

The purpose of the registry is to maintain and preserve sound recordings and collections of sound recordings that are culturally, historically or aesthetically significant.

Two months before the March on Washington, President John F. Kennedy met with civil rights leaders to express his fear that the event would end in violence.

Kennedy told organizers that the march was “ill-timed,” as “we want success in the Congress, not just a big show at the Capitol.”

King and the other civil rights leaders insisted it should go forward, with King telling the president, “Frankly, I have never engaged in any directaction movement which did not seem ill-timed,” according to historical accounts.

JFK ended up endorsing the march but ordered his brother and attorney general, Robert F. Kennedy, to ensure security precautions were taken. In addition, civil rights leaders decided to end the march at the Lincoln Memorial instead of the Capitol, so as not to make members of Congress feel as if

Officially called the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the historic gathering took place on Aug. 28, 1963. Some 250,000 people gathered in front of the Lincoln Memorial; among many performers were Joan Baez and Bob Dylan (below).

they were under siege.

For Barbara, the day had been full. Feeling euphoric, she and her Freedom Rider friend made it back to the bus without incident. The driver knew everyone was hungry and stopped at a hamburger stand at a place called Royal Oaks in Virginia, Barbara remembers.

“We were very hungry,” she said. “A man came out and said, ‘We don’t serve coloreds here,’ and he sent us away. It was the first time I had ever experienced this kind of racism.

“The place he sent us to was an awful little place that couldn’t accommodate all of us, and we were there a long time. It had one bathroom, and lines were long.”

That experience reinforced Barbara’s certainty that attending the march was worth the sacrifice—her mother’s fear for her safety, the discomfort of the day, hunger, heat, fatigue, all of it.

“No one should be treated like that,” she said.

While she herself had never experienced racial segregation before that day, she was familiar with other types of racism, including prejudice in the workplace.

At 18, Barbara joined the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) and became a volunteer decoy to uncover companies that discriminated against Black people by only hiring whites. She discovered firsthand that Black people who had the same education and qualifications were passed over in favor of white applicants.

Barbara “was treated very differently” when she applied for clerical jobs at big well-known companies, she said.

She ended up working for an insurance company based in New York City because there was nothing to be found in New Jersey, where she lived with her parents and nine brothers and sisters.

“We were a church-going family who believed in Christianity and in the principles of civil rights. All my sisters and brothers were part of the movement and protested in one way or another. That spirit of involvement was all around me and in me,” she said.

Her parents had moved from Georgia and South Carolina to New Jersey in the hope of protecting their children from the Jim Crow south. In some ways, they were successful. Barbara’s mother often told her that she was grateful that Barbara had not personally felt the brunt of the racial hatred experienced by her parents in the south.

Barbara and her brothers and sisters attended integrated schools.

One brother became the first Black vice president of a bank in his city; another was an engineer. A third was the director of a college in Texas, and a fourth, a respected Baptist minister.

A year after the March on Washington, Congress enacted The Civil Rights Act of 1964. It ended segregation in public places and banned employment discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin.

It is considered one of the crowning legislative achievements of the civil rights movement.

Today, Barbara proudly acknowledges that she is part of the civil rights movement that led to that landmark reform and continues today as the blight of racial inequality persists.

After Peter, Paul and Mary’s performance at the march 59 years ago, Mary Travers said: “It is so easy today to not see the things that are happening around you because you’re too busy, because you’re doing something else.

“But . . . we do not have freedom as a gift. It’s not given to us as a God-given right. It’s something that you must take, and you must fight for, and you must preserve this liberty. And that’s what the song (“Blowin’ in the Wind”) speaks of. Of listening, and watching, and being careful not to lose this liberty.”

Her words ring true today.

Two months before the March on Washington, President John F. Kennedy met with civil rights leaders to express his fear that the event would end in violence. Kennedy told or- ganizers that the march was "ill-timed," but Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the other civil rights leaders insisted it should go forward.